To Chang Mai

To Chang Mai

I am becoming increasingly puzzled by those labels given to countries: 'developed' and 'developing'. Does any country ever stop developing? And what are the criteria which makes one country 'developed' and another country 'developing'? If it is poverty, I have seen more destitute people and industrial dereliction in the U.S. than in Thailand. If it is access to education, Thailand has as good a literacy rate as France. If it is good communication, I don't seem to have as many problems with my ISP here in Thailand as many of my friends seem to have in U.K. Is it transport then? I recently forwarded to many of you a witty letter which appeared in The Times from a man who had lived in Vietnam and described the efficiency of his various modes of journeying from his village to Hanoi compared with his more recent experiences travelling from Liverpool to London.

I have just been to Chiang Mai. I could have flown (45 minutes) but I opted to go by train; by overnight sleeper to be specific. 2nd class, if you must know. I had pre-booked my ticket at a special counter for tourists from a charming man in neatly pressed trousers, an immaculate shirt and tie who spoke English. Does any British or American terminus have such a ticket counter for Francophones? There was a notice by the counter which said if I was not entirely satisfied with the courtesy of the service provided I should ring this number... I didn't even think about it.

And so to Hua Lampung Station last Thursday evening by taxi which drew up at the side entrance of Bangkok's answer to King's Cross (and looking very like it) to provide me with a short walk to Platform No. 5 for the Chiang Mai Express. Like all large termini Hua Lampung is a riot of people, food stalls, vendors and their attendant noises echoing round the vast, domed train shed. Electronic destination boards flashed and changed in an instant as arrivals and departures occurred. I was early so I ate good Thai food at one of the scores of restaurants in the station concourse: 20 baht (33p or 50c.) The train - all aluminium, tinted glass and whirring air conditioners ('made by Daewoo in Korea 1996') - backed slowly down the platform as we waited. A train conductor stood on the steps of each carriage and welcomed us all aboard as he showed us to our seats. The second class sleeping arrangements were much as Marilyn Monroe found them on her trip to Florida in Some Like it Hot. The seats converted into double bunks - one up, one down, lengthways either side of the aisle, with curtains providing us with privacy. On time, give or take a minute of two (this is Thailand), the train pulled out slowly and passed through Bangkok on its way 750 kms to 'The Rose of the North' - Chiang Mai.

Most exits from city railway termini are depressing affairs (Euston is by far the worst of any I know); dereliction, old sleepers, unused cables and track are piled by the side, weeds and wild shrubs grow in the cracks in walls, graffiti covers every available space and there is always trash, plenty of trash. Not in Bangkok. As it gathers speed outside the station the train passes right beside the King's palace. It was as though we were aboard a Disneyland train. Neatly tended flowering bushes, herbaceous borders of lilies and Bougainvillae lined the route. The track was spotless. For some miles, wide tree-lined boulevards followed the track on either side. The King has his own private, cream and gold railway station from which he may step onto his Royal Train. The rest of his subjects get the vicarious benefit. Not until we reached the suburbs of Bangkok were slum shacks, those ubiquitous parasites of railways, evident. It occurred to me that poor citizens build their hovels on railway land - so close to the train we could have touched them - because railway land is a sure bet for a long stay; it's the only land area in a 'developing' city one is certain of not being developed and thus evicted.

There was no restaurant car on the Chiang Mai express. That is far too uncivilised. Three of fours waiters constantly ran up and down the aisles with offers of drinks, snacks and even four-course hot meals which were served at our table (British railway companies please note!). We need not have stirred from our seat for anything (except the obvious): would Sir like some fresh-pressed orange juice? Or sliced fresh fruit? Some hot spring rolls perhaps? Or the menu? Since I had eaten prematurely at the station I declined most of these offerings but asked for a cold beer. ('We have Singha, Heneiken, Amstel, Tiger. Which brand would Sir prefer?') It came to my table in an ice bucket. Others round me tucked into curried prawns, clear chicken soup, spicy pork and noodles. I can't vouch for its quality, but it looked good enough to eat.

I thought I was lucky: I was the solitary occupant of my side of the aisle and so was a Japanese gentleman opposite me. But up the line at Sam Sen station our luck ran out. A Chinese grandma, her daughter and her two small children clambered aboard and deposited themselves next to us. I smiled sweetly but groaned inwardly. If you have not experienced it, a Chinese family on their travels are the noisiest things this side of a rock concert; they do nothing - talk, eat or sleep - quietly. Chinese children are spoilt rotten and are allowed every excess which their cunning minds can contrive. Foreigners are fair game for anything up-close-and-personal. They also never have suitcases, but carry all their worldly possessions (and some more) in thousands of plastic bags and cardboard boxes with which they proceeded to cover every available surface and block the aisle. The waiters, ever courteous and Thai, ignored this obstruction and managed to flit lightly over them with a tray full of four bottles of beer, two bottles of water and a bowl of steaming noodles. How they managed to resist the temptation to cuff the screaming brats en passant, I shall never know. It was 8.30 p.m. and to my dismay Madam Chou signalled to the attendant (whose only job it was to do this) to make up the beds. He politely asked me to remove myself while the Rubik's cube of seats and backrests was transformed into two, long bunk beds with spotlessly laundered linen sheets and an enormous, cream blanket. 'What! Now?' I was horrified. 'But it's only 8.30!' He smiled at me sympathetically but Madam Chou was not to be crossed, and I sullenly found myself an unoccupied seat down the aisle. Of course, the conversion to beds so the wee ones might get their rest was pointless; the brats continued to scream around for many an hour yet. Every time I caught the eye of Madam Chou and daughter Chen, I glared at them meaningfully. It had no effect. The common-as-muck Chinese have this one thing in common with rhinoceroses: their hides.

I found myself sitting opposite a friendly Thai man in his early thirties who lived in Chiang Mai. Having discovered this was my first trip there he waxed lyrically about his home town as most people do about their home towns. He did something with computer software (every second man I meet in Thailand seems to do something with computer software), came reluctantly to Bangkok ("So noisy! So dirty!") about three times a month on business, and perchance to see his girlfriend who is a stewardess for Korean Air, and who rarely gets enough time off to make the rip to Chiang Mai. He was married before, he told me, but it went wrong somehow. 'I work too hard to get money. It was wrong. Better luck this time! Eh?' He beamed at me. 'Ah yes.' I said sympathetically. 'It's always better to work to live than to live to work.' I don't think he understood a word of what I was saying.

Since it was now 10 p.m. and with nothing to see from the window except the odd house light drifting past, and my conversation with the young man now all but exhausted, I decided to turn in. Resisting the temptation to tread on the head of one of the brats I clambered up to the top bunk and sorted myself out. Then I clambered down again for I had forgotten the wee and teeth-cleaning. The toilets were clean and well stocked with the usuals. There was even a choice between a squat loo (for the die-hard Asians and any French on board - of which there were surprisingly many) and a 'Western' sit-upon. This I considered the height of thoughtfulness. The Thai gauge (skip this bit if you're not a railway buff) is narrower than the standard 4'81/2". I didn't actually get out and measure it, but guessed it to be about 1m. It gave for a rocky ride. Not all the track was modern welded rails either so the combination of the rocking motion and the clickety-clack sent me off to sleep with George Orwell's Burmese Days falling gently from my grasp very quickly. When the train gave a bang and judder as it left some intermediate station or other, I woke and removed my glasses. Oh! Oh! Falling asleep with my glasses still on! What an old buffer I am becoming!

First light. And we were now crawling on a winding, single track up a mountain pass. I now understood why the journey to Chiang Mai was 6-8 hours by car but 13 hours by train. So steep were the inclines, so sharp the bends that we were hardly moving. But the view was wonderful. Mists curled round the jungle. Was that the shadow of a tiger I saw just then? Vertiginous drops and breathtaking bridges over gorges wakened the senses quickly. Would Sir like breakfast? Yes indeed! Sir would like - let's see now... - two fried eggs, bacon, sausage, toast and coffee seems about the ticket. And in ordering thus, I broke my rule never to have western food which is not cooked by someone who knows what western food is like. My rule proved steadfast yet again. The sausage was inedible, the toast was limp and very white and the jam some sort of pineapple so sweet it was tasteless. The final calumny was at the very moment we were passing a grove of very healthy-looking coffee trees I was served a cup of hot water with sachets of Nescafé and Coffeemate to mix myself. (In Sumatra they grow, as you know, the best coffee in the world. It's fearfully expensive. In the airport in Medan you cannot get a cup of freshly ground coffee; only Nescafé. It's 'modern', you see. Only poor people drink real coffee in Sumatra... And while I'm on the subject: only the most destitute will use black pepper in Sarawak. They are the sweepings from the barn floor - the shrivelled peppercorns past their prime which nobody in Sarawak would be seen dead mixing with their food... If you really want to be 'correct' you should use only white pepper, just as my mother did, or green peppercorns on the stalk put in the casserole. And while I'm still on the subject: brown rice is an absolute no-no for anyone who knows anything about rice. Thailand has the best quality rice grown anywhere. The Thais know all there is to know about rice. They feed unhusked, brown rice to the pigs here!)

At the scheduled time of 9.25 a.m. we squealed into Chiang Mai station; the end of the line. I had been served well, I had slept well, I had seen many sights and we had arrived on time. The cost of this air-conditioned, operatic and extravagant entertainment of 468 miles? 610 baht - a little less than £10 or $15. Who is living in the 'developed' world and who is not?

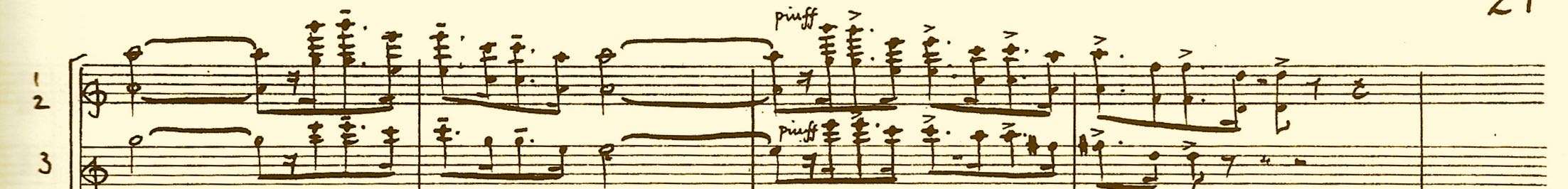

A Thai friend who seems to have houses and apartments dotted all over Thailand had very kindly offered me his condominium in Chiang Mai. ("Just give the maids 100 baht to clean the place up, and send the sheets and towels down to the laundry when you leave...") I managed to get the tuk-tuk driver to understand 'Thanon Suthep, Soi Ha, Hillside Condo 1" and I set off through Chiang Mai. The city is 700 years old and in many ways resembles York: a walled university city with some of the mortarless brick bastions still in place, a moated city with wide, straight moats on four square sides. Gates to the old city are sited in the middle of each length of the square. Inside and outside the old city the whitewashed walls of temples rise up in every direction just as churches do in York. But in Chiang Mai the temples are not redundant, converted into museums and arts centres, they are vibrant, active monasteries. You can't walk down any street in Chiang Mai without coming across a gaggle of saffron-robed monks going about their daily rituals. Some are more monkish than others: I caught two having a quick fag (cigarette to my US readers...) crouched behind some potting sheds in a monastery garden I had sauntered into... Whereas the traffic in old York is a shambles - especially in The Shambles, Chiang Mai municipality has been much cleverer. On the outside of the moat a wide boulevard runs round the square of the old city, and inside the walls another road runs counterclockwise. Every so often a bridge crosses the moat to allow traffic to do a 'U-turn'. You simply get on the road one way and keep on going round until you get to where you need, take the next U-turn bridge and come back on yourself to your destination. It's the easiest thing to find your way around. I know this because I hired a motor-bike and bombed my way round miles and miles of the city's streets. It took me back to my glorious early Bali days when I used to careen round the island on my motor bike. I'm glad to say I hadn't lost the knack and live to write this tale. Thai friends had given me various names on which to call. Khun Ad was my first. She is a puckish piano teacher educated in The States and the sweetest, kindest person one could wish to meet. She immediately informed me there was a string quartet playing in a privately owned auditorium that evening. She would take me. ("Pick you up at seven sharp. Ya?") The idea of a privately owned auditorium is alien to us; we just don't have people willing to part with that kind of money unless they are the kudos-seeking super-rich of America. Khun Wichit is an antiques dealer - that's all, and he grew his business from nothing - who, enthusiastic but knowing little about music, first bought an upright piano and started some concerts in his antiques gallery. Somebody told him (politely - this being Thailand) an upright piano wasn't quite good enough if he wanted to attract top-quality recitalists so he bought a rather nice 7'6" Yamaha grand. Somebody else told him the gallery wasn't quite suitable either; it was too crowded with objets d'art to be effective. So, last year, he built himself a small but lovely concert hall just down the road from his gallery which doubles as a photograph exhibition space. He is completely self-effacing about it; I didn't even know it was he who had made all this possible, when first introduced to him, and only found out afterwards when he invited this complete stranger to dinner at an Italian restaurant along with the string quartet. This is Thailand.

The quartet were young string players all educated abroad and all excellent. The viola player afterwards told me he was really a violinist but had taken up the viola only last year so they could form this quartet. ('It was the alto clef which confused me. I got the hang of the fingering quite quickly...') In a year he had learnt sufficiently well to join the quartet in playing Beethoven Op 59 in C - and play it superbly the night I heard them. I have rarely heard a quartet with such energy and commitment. I sat next to Kit Young at the concert. She was born in Thailand, being the daughter of the then US Ambassador, and now is the wife of the US consul in Chiang Mai. She has lived more of her life here than in the US. Of course she speaks Thai, and is in the piano department of the music faculty of Payap University. After the quartet had played a very impressive set of Enigma Variations by a Thai composer, Kit asked me what kind of music I wrote. 'A lot like that.' I answered, and nearly added 'What-what!' before I realised its Blimpish connotations. It was the best compliment I could think of to a fellow composer for the music we had just heard.

In the interval and afterwards many came to say hello to this stranger in their midst. Chiang Mai is a small town (500,000) for classical music lovers and any new face is conspicuous. I can't now remember all their names. One was a young painter who had studied at St. Martin's School of Art in London. "Did you enjoy London?" I asked by way of small talk. "Not much." She replied unnervingly. I pressed no further, but she proffered a little more: "...too many egos and not enough good, proper teaching." I think I know what she meant. We fell silent. Her mother saved the day: "What do you think of our little concert hall?" "I think its marvellous." I said brightening. "We have nothing like this in England." "But you have Glyndebourne and The Maltings and all those wonderful arts centres!" She exclaimed. She knew her stuff. "Yes..." I said doubtfully. "But they always seem either to collapse under the weight of debt, or puff themselves up into pompous and alienating places." I was thinking particularly of the Snape Maltings. I went on: "I do hope this place stays like it is: small, private and chummy. You know the English word 'chummy'?'" "Oh yes!' She smiled. "I lived in Kent for a number of years." We both knew what we both meant by 'chummy'.

Since there has been a good Thai restaurant in Grimsby for many a long year, I can't imagine why I was surprised to find not one, but two good Italian restaurants in Chiang Mai. It's that old, Empire arrogance still lingering even in me I suppose: it's OK for the fuzzy-wuzzies to seek a better life in God's Own Country by opening up a restaurant or two, but not the other way round. Letting the side down - what!? (But then perhaps Italians are not quite on the 'right' side...) But it was to the imaginatively named 'Restorante Italiano' that Khun Wichit had invited the quartet, a cardiologist whose name I've now forgotten and me to dine after the concert. (I was the tag-along: Khun Ad had whispered in Khun Wichit's ear that I hadn't eaten and was hungry. I had demurred at the first invitation - I didn't want to intrude - but my presence was insisted upon. This is Thailand...)

The red wine flowed, the home-made pastas and pizzas came and went. The conversation was youthfully lively, and I am old enough now to start impressing the young. The cellist was agog that I had lived at Brinkwells for so many years, the birthplace of his favourite concerto. The second violinist, a charming girl home on leave from her studies in Colorado, pumped me for anecdotes about the few occasions I had met Benjamin Britten. The leader was thrilled that I had met Walton, the composer of one his favourite violin concertos. I hadn't thought until now that I am a walking history book; but for people in their early twenties I am. How quickly one changes from being the fresh-faced student sitting agog at the feet of the alpine Herbert Howells to being - if not the next generation's Herbert Howells - certainly something like the junior slopes! (Kit Young had asked me if I had known Paul Bowles. No. But I know a man who had. It was enough...) I had a most happy time with them all. The cardiologist drove me home in his circa 1970 VW Beetle. No breathalysers in this part of the world! Most of the police are themselves half-cut at that time of night anyway...

The next day, Saturday, after the mid-day heat had subsided (it was up to 38 degrees) I donned my helmet, sat astride the bike and roared into the cooler air of the mountains. I was bound for Doi Suthep a temple and monastery perched on a mountain top overlooking Chiang Mai. At various resting points along the steeply winding road, I paused to take in the view. I saw the airport with toy air-planes landing on its runway, white tower-blocks and winding rivers appeared out of many, many trees. The two universities seemed like hugely spacious garden suburbs on the edges of the city. Chiang Mai is an understated city that can be proud of itself. Doi Suthep is very famous. It houses a relic (a bone) from the Buddha. Buddhist pilgrims come from all corners to make merit at this shrine. The temple was founded in 1358, so ranks alongside many of our own cathedrals in antiquity and hallowedness. Like many hilltop temples the steep steps from the vendor-saturated road to the temple compound are daunting to all except the super-fit. The monks have recently, thoughtfully installed a cable car. This is because they are rolling in money and know how to spend it to make even more money.

If that polite little notice you see at the west doors of our cathedrals ('...it costs £50 an hour to maintain this ancient cathedral. Will you give just a little?...') gives you a twinge of conscience don't go into a Thai Buddhist monastery; you'll be flat broke by the time you come out. Every conceivable flat surface, in front of every statue of the Buddha (and there are hundreds of those), at every turn you are confronted with another offertory box: '...for the poor', '...for the education of hill tribes people'...'...for the upkeep of the temple' '... for the sick' etc etc etc. And Buddhists do give. By the hundreds of thousands of baht they give. It is a way of making sure your sins won't turn you into a rat for the next life. Been a crooked government minister? Build a pagoda! - The more lavishly gilded the better. That'll see you right for the next life. The hundred-foot-high chedi which houses the Buddha's relic is at the centre of Doi Suthep's elaborate conglomeration of buildings. It is completely covered in gold. White marble dons every floor, every building down to the humblest dormitory is carved, lacquered and gilded. From some statues of the Buddha little flakes of gold leaf twittered in the mountain breeze. Someone had recently but inexpertly stuck on yet another patch of gold leaf. Some of the statues were so encased in these patches the physiognomy was barely recognisable. From anywhere you stood, Doi Suthep oozed Money. And I thought of the dusty corners of our own cathedrals and parish churches, a few broken chairs put there out of harms way; of grimy organ lofts that hadn't seen a squirt of Ajax in a hundred years; of faded vergers with dirt encrusting the bottoms to their cassocks; of vestries with cupboards last varnished in the reign of Edward VII. Nobody cares. No-one really cares. They will paint the outside of their own homes first before thinking of donating the paint to the church. (But who, in any case, will set aside the time to do the painting?) For the Buddhist it is the other way round: see to the temple first, and this merit-making will see to it you will not go through life empty-handed. As Henry VIII perceived, such wealth in monasteries leads inevitably to corrupt practices. And there are many stories of abbots with their own private collections of vintage Mercedes cars, or harems, or catamites. (One monk in Bangkok was recently caught going into a hotel wearing a major's uniform and was arrested for impersonating a serving officer. He explained his mistress liked him to 'dress up'...) And, just like the Reformation, there are growing signs of impatience by the populace of their monks. Hardly a day goes by without a new story in the Bangkok Post of yet another wayward monk being caught either 'at it' or with his fingers in the till. The commentary writers tut-tut appropriately.

In some of the courtyards I had observed a number of boys - the youngest maybe 10 and the oldest, the supervisors, no more than 14 or 15 - mopping the marble floors with huge, wide cloths. They were not dressed as monks but wore rather ragged, ordinary clothing. In the cafe, too, girls of about the same age-range stood behind the counters serving and collecting the cash. All of them - boys and girls - had a rather care-worn expression. Their smiles were not those of carefree childhood. When they were not working they sat immobile and expressionless. Later I passed a monk in his thirties sitting on a small dais in an anteroom with a little sign by his side: 'Chat with a monk. English spoken'. So I asked him about the children. He told me they were from certain villages in the mountains, usually from poor families who came to this particular temple to help with the chores. I nodded. "Do you educate them here?" I asked. He replied in the negative; they came at free times - school holidays and so on - if they still have a school to go to, but many have stopped at 12 years old. I pressed a little further: "So you give them pocket money, feed them, clothe them and so on?" No. The poor families pay a little something to the temple authorities for the privilege of their being there. "...it's only a very small amount." The monk added, by way of excuse. I wanted to say 'So they're slaves?' but held my tongue. I now understood the root of the expressionless faces these children had. Unloved at home, they had felt abandoned by their parents when packed off to the monastery. And at the monastery were they loved? I doubted it; unless they were 'loved' in quite the wrong way. I had caught one white-robed, shaven-headed nun (themselves merely handmaidens and drudges for the monks) speaking sharply to one of the girls in the café. How much abuse was there, I wondered, behind those gilded, lacquered doors after the tourists had left for the day?

On Sunday I met Kit Young again. She showed me round the music department of Payap University. It was a few ramshackle buildings - some wooden - tucked behind a much grander, modern building devoted to theology. It came as no surprise to learn the university had been founded by Christian missionaries. Kit has been devoting much of her time of late to two projects: a summer camp for young musicians who live out in the sticks and who therefore have little access to live performances; and piano tuition to keen students from Burma, not very far away as the crow flies but a million miles in development and access to the outside world of the arts. In Burma there are no musical instruments, no new ones at any rate, and no-one to repair the old ones. They simply can't afford it. So ravaged is the country by more years than anyone cares to remember of military rule and economic mismanagement there is nothing left of the old ways of culture and high art. She told me of a teenage boy who had practised alone on a small Cassio electronic keyboard until he had mastered it. Having no-one to explain the correct ways, he had learnt a very idiosyncratic form of fingering. Kit paid for him to come over the border and spend a few months at Payap to absorb the music that was happening there and get some learning under his belt. Within a year he had gone from nothing to Grade VI. Not that he could have been tested. The Associated Board and the other examining boards have long since abandoned Burma. The Burmese can't afford the fees, and it would be asking too much of the Associated Board of The Royal Schools of Music to do something altruistic with the squillions of pounds it earns every year.... (Queen's Award for Industry...) Perhaps there lies a truer definition of 'developed' and 'developing' countries. In the 'developed' world the 'haves' have as much as they want, and the 'have-nots' have enough for their needs. In the 'developing' world, the 'haves' have more than they want, and the 'have-nots' have less than they need.