A Rural Thai Wedding

I have had the most extraordinary weekend with a new friend with the improbable name of 'Golf'. He is a teacher of Thai grammar in a secondary school and comes from Phichit half way up in the rural north of Thailand. Despite his youthful 23 years and an M.A. in Thai linguistics, Golf was anxious that I should accompany him on a visit to his home town to attend the wedding of a family friend's daughter. He failed to tell me before we left, however, we would have the company of two of his girl friends for the four-hour journey in his car. You've probably never heard Thai girls talk; they have a nasal twang to their inflections and do it very loudly, interspersed with high-pitched shrieks of laughter as they battle each other to be heard. In a small car this can be unbearable, and it was - for hours on end - especially since 99% of it was incomprehensible to me.

It is, perhaps, axiomatic that the more corrupt a country is the uglier will be the scenery. Zoning laws which stick and green belts are simply unheard of in Thailand, so it is scores of miles out of Bangkok before a green field heaves into view. This part of Thailand is the huge flood plain of the mighty Chao Praya river, so not even hills vary the aspect. The only points of interest are the roadside restaurants. A thirty-foot neon lobster will subtly tell you this one specialises in seafood. A fifteen-foot concrete green papaya is a clue. For four hours the straight concrete roads and the view of rice paddis and sugar plantations hardly altered at all.

It was dark when we got to Golf's town; an ugly conglomeration of concrete shop-houses, sugar factories and overhead cables and with all the grace of Circleville Ohio - and I had to make polite conversation to his parents and innumerable rabbits, friends and relations who had gathered to welcome this special guest. None of them spoke any English. It was so painful I nearly turned round and went home. They viewed me as if I were some Martian, and giggled uncontrollably every time I attempted some Thai.

Golf's father is Chinese (his mother is Thai) and it is always surprising to me how tastelessly and uncomfortably the Chinese live. This family is not poor - his father owns a gold shop - but the Chinese never spend money on the comforts of living. So we sat on hideously varnished hard chairs ranged round the tiled walls of a cavernous room which echoed to the still-shrieking voices of the girls. Oh! for a cushion! And ear-plugs! Bathrooms, too, are not something on which the Chinese feel the need to be lavish. One was open at the top to the kitchen next to it (what would the health inspectors say!) and the other was on a landing. Every flatulent embarrassment hurtled round the hard walls. The squat loos I have never liked; I endured them enough in Bali to never want to see one ever again. The bathing was the same too: a tank of water and a bucket. Nowhere to hang clothes, no basin to hold water to brush your teeth or shave (most Orientals shave about once a month) and, of course, no simple means of cleaning oneself. I have never discovered the secret of how they do it without getting all their clothes soaking wet. At least the sparsely furnished bedroom was air-conditioned, but the bed was so hard one might as well have been sleeping on a plank. I noticed what little furniture decorated the room was all new and so was the pale green gloss paint on the walls. I wouldn't surprise me to learn they redecorated the whole house just for my visit. There is no possibility of the Chinese ruling the world; they just don't have enough sense of style.

Golf was manic with nerves. Every few minutes he would ask me if I was all right. As is our Western custom, I had brought Golf's mother some flowers. She didn't have a vase and plonked them still in their cellophane wrapper in a jam-jar. Golf told me later it was the first time in her life anyone had ever given her flowers. Crazy foreigners! We arrived very late in the evening but this didn't stop us from going out again to visit the home of the family of the wedding. The town is the size of Petworth, so it took only a few minutes to get there. Across the narrow street a marquee had been erected (British and American authorities: 'I'm sorry sir, but you can't erect that thing in the street, sir. Regulations...') and men were already getting down to the serious business of whisky. Whisky is made locally here; is cheap, deadly and the preferred tipple. The house itself was a small clapper-board concrete box, but had been decorated from top to bottom with yellow roses and ferns. Outside on an easel was a large framed portrait photograph of the happy couple already in their wedding finery, slightly fuzzy and unfocussed; a metaphor for their life, I thought. There is a high rate of divorce in Thailand and, if that is not the option, many men take 'minor wives' eventually. The bride, dressed incongruously in a white Christian bridal gown, was 20 Golf told me. The groom, in a white satin suit, was 23. The whole aspect - the street with its concrete houses and messy overhead cables, the marquee, the roses, the portrait, the clothes - was wholly American mid-west; but if you suggested this, every Thai would protest this was genuine 'Thai culture'.

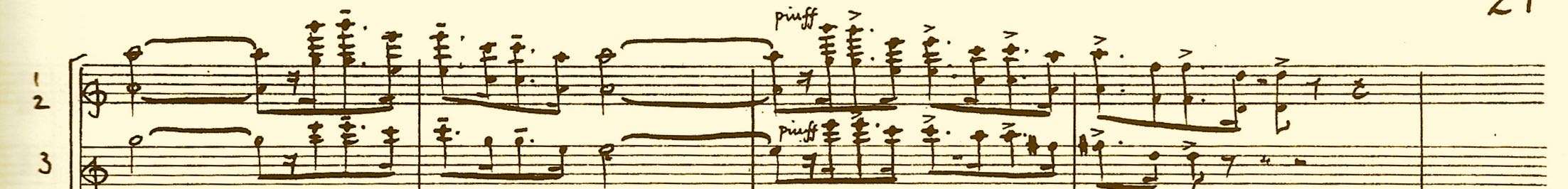

We were up at seven because Thai weddings start early. (The bride had started her make up and hair-do the night before.) When we arrived, a band of musicians playing ancient trumpets, clarinet, saxophone and a bass drum were already working through their repertoire of Sino-Thai tunes. A bank of speakers as tall as the house stood outside and a voice which could be heard all over the town kept up a constant commentary. The racket was hideous and deafening. Inside the rose-covered house a line of monks sat cross-legged against the wall and wafted themselves with elaborate fans. Only when the commentator drew breath could a snatch of some chanting be heard from our seats under the marquee's awning. Food, of course, was brought immediately; but at eight in the morning I was not quite ready for a hot green papaya salad, or coagulated pig's blood. There was a dish too of some kind of minced brown meat mixed with many red chillies. Golf tried to explain what it was without knowing the English name: "Big bird... run velly fast... no fly... velly delicious." At last I got it. It was ostrich. I had seen a sign to an ostrich farm on the way up. "Eat! Eat!" everyone cried. I demurred, hoping I might spy a croissant and some thick cut marmalade at this time in the morning. Some hope!

The groom's father, pony-tailed and in cowboy boots, came to sit by me. He played drums in a hotel band. "If I like a town. I stay there and play drums. If I don't like it I move on." His wife, he explained to me, had divorced him years ago and was now living in America. She was not here. I implicitly understood him to mean that her visa and work-permit situation in America was not conducive to her leaving. She probably would not be allowed back in again. It is not all roses for the illegal immigrants of the world. The one moment any mother longs for - her son's wedding - had been denied her.

At about 9 a.m. a procession began to form in a vacant lot a couple of hundred yards from the house. A long swathe of cloth had been laid across the dusty, dry grass and offerings were placed on it; whole chickens and silk on chased silver dishes - much like the Hindu ceremonies I had grown accustomed to in Bali. At the far end under a parasol stood the groom. It was the first time I had seen him in the flesh. The band positioned themselves at the head of the procession and old crones, dressed in their Thai silk finery (another piece of faux Thai culture; the completely moribund silk industry was restarted by the American Jim Thompson in 1946), began to improvise a dance, stepping in time and curling their hands and wrists in the air. Suddenly I found myself standing next to a kathoey wearing men's jeans but a flowery blouse, bright red lipstick, plucked eyebrows and mascara. He smiled coyly at me and I smiled back. "Where you come flom?" He lisped. "Anggrit [England]" I replied. "Dtee chan yuu tee Krung Thep" [But I live in Bangkok]. "You velly handsome." He said. "Thank you." I smiled and moved away. I wondered what on earth would happen in Petworth if one of the male guests turned up at St. Mary's wearing make-up and a woman's blouse. The bashful groom in his crumpled satin suit shuffled along at the end of this motley procession which headed for the house. Unfortunately the monks had finished whatever it was they were doing, had climbed into the back of a truck and were heading in the opposite direction towards their monastery. Implacable force met immovable object. There was some consternation; the marquee and we guests were taking up half the width of the street and the truck took up the rest. The commentator came into his own and, shrieking at 120 decibels, directed the traffic. Half the town must have been in chaos as they obeyed these unseen instructions; his voice was probably heard a hundred miles away.

There was no wedding ceremony as such. No 'till death us do part' or anything like that. At the gate to the house Golf and his aunt held a long gold chain across the entrance. Any guest could pay some money to cross this chain to enter the house and bring good luck. Finally the groom entered and emerged a few minutes later with his bride. She must have been up all night having been prepared for this moment the night before by two more kathoeys, cousins of the bride who were now hairdressers and make-up artists in Bangkok. They now stood beside their perfect creation guarding jealously every potentially smudged eye-liner and recalcitrant wisp of hair. Everything in Thailand is about surface. What goes on underneath is inconsequential. By ten o'clock it was all over and guests having eaten well, began to creep away. What the Boeing 747 commentator had to say at this point I have no idea, but he kept talking just the same. We waied graciously to the father of the groom (I don't think I ever met the bride's parents) and headed for Golf's car. But we would be back: later that evening there was to be a 'gala'.

Behind the houses was a huge wasteland of dry grass and dusty earth backing on to the main railway line from Bangkok to Chiang Mai. This was the site of the 'gala', or wedding reception. We arrived at about six and waied graciously again to the bride and groom as we passed between two houses onto the waste ground. The bride was still as impeccable as ever and I wondered if she had been trussed up in all this finery without a break since last night. (Now there's a challenge for a squat loo!) Even though it was quite early, already many of the forty-or-so tables of eight were occupied. To my horror I saw - and heard - that the 30-foot bank of speakers had been moved and paired up with their stereophonic twins either side of a very professional-looking stage. And lo! Mr. Commentator was at it again, but this time several decibels louder. "Couldn't we sit a bit further back?" I pleaded. But my plea went unanswered, or unheard, for we marched resolutely down to a table nearest the stage. There was nothing for it, and I didn't care what I looked like: I stuffed two pink paper napkins into my ears.

One can only admire the Thais for their ways with food. From nothing more than a field kitchen, dishes of the most exquisite variety, including whole steamed fish cooked with shallots, garlic and ginger (and more ostrich meat), just kept on coming to our table. We ate, and we ate and we ate. But no-one at our table (and few elsewhere, I noticed) drank any alcohol. It was available, and I had a local beer. Everyone else drank Coke or Sprite - just one more 'traditional Thai custom'. At the moment I thought I simply couldn't bear any more of Mr. Commentator's inane gabbling, he stopped. But worse was to follow: it was Karaoke time. Local youths got on to the stage and, one by one, strutted their stuff. This 'traditional Thai custom' is difficult to describe in words. You need to hear just how out of tune Thais can sing to appreciate the full horror of a twelve-year-old boy dressed in silver sequinned suit battering out at 125 decibels the latest Kylie Minogue number to his adoring family and friends. Some had rehearsed elaborate numbers which included their fourteen-year-old schoolmates gyrating in formation, dressed in Hot Gossip creations which left little or nothing to the imagination. It was both horrifying and alarming. That such young girls and boys should be so sexually explicit to the delight of their family sent shivers down my spine. Or perhaps we've got it wrong and are too concerned and too protective; I just don't know anymore.

Conversation was, of course, impossible, but that didn't stop most of the guests from talking very loudly into each other's ears throughout the speeches. First the honoured guest of the party, the Mayor of the town, gave a speech at 125 decibels to a completely indifferent audience. This is quite common in Thailand. I have even seen television film of the Prime Minister give a speech to a gathering who, even right behind him, talked incessantly to each other. Most Thai teachers use megaphones and loud-hailers in classrooms. The mayor, too, sang an obligatory song; cringing in its ineptitude and so out of tune it was unrecognisable to me. Mr. Commentator giggled his way through introductions to the bride's father, the bride's mother, the bridegroom's father and various family and friends. All gave speeches, all sang songs and no-one listened to any of it - except, of course, peripherally, since one couldn't avoid hearing it at that volume - and no-one clapped. A train on its way to Bangkok hurtled past and hooted. Everyone got up and waved to it. The passengers waved back. The speaker carried on speaking through the speakers.

In this 'traditional Thai wedding' we did have some traditional Thai dancing. Beautiful girls in gilded head-dresses and elaborate costumes swayed and curled. But nobody watched it. It was as incongruous as a chest of viols suddenly starting to play Orlando Gibbons in the middle of a Romford knees-up. But a Thai wedding does have one tradition of which I heartily approve. After all the speeches were over (but still with a few straggling Karoake enthusiasts determined to have their 15 minutes of limelight) the bride and groom walked with a few youthful aides from table to table. To each guest they said a few words, gave from a huge basket a small trinket and waied graciously. In return the guest waied graciously and gave the bride a small envelope. As this little procession came closer to our table Golf turned to me and into my napkin-stuffed ear shouted "Give me 100 baht" and he produced an envelope and added my 100 baht note to others inside. I understood immediately. We were paying for the party! How many times has one heard of parents in England or America at best re-mortgaging their house or at worst getting heavily into debt to pay for their daughter's wedding? Here, it seemed to me, the Thais were being eminently practical and sensible. No-one could expect such an extravagance to be the burden of one family, and no-one did.

After this little ceremony was over most guests and we began to leave. We waied graciously in ever direction: the cooks, the parents, the security, the cooks again, the owners of the houses through which we must pass to get to the road, the parents and any friends we met - everyone who might conceivably need a wai got one. Not everyone left immediately, and as we trudged wearily into Golf's house, we could still hear from over the rooftops on other side of town some piping treble singing mournfully of lust and love.