Letter 5

If you look out from our vast verandah out across the rice terraces, beyond the last Raja of Karangasem's ultimate folly, the water palace at Tirta Gangga, beyond even the range of hills reminiscent of nothing less than a palm-treed Shropshire on a clear day, if you look beyond all these wonders you reach the the most spectacular of all: Ganung Agung, the home of the Hindu Gods on Bali. It is still an active volcano which last made its presence felt in 1963 with a thunderous roar, six months of earthquakes and thousands of deaths. Although it lost nearly a thousand feet when the top blew off on that eventful day, it is still over 10,000 feet high; higher than most of the Alps. But unlike the Alps, Gunung Agung blows its 10,000 feet all in one go; no messing, no infant hillocks or junior slopes, just straight out of the sea.

Squatting precariously high on the slopes of this marvel is the village of Juwuk. The soil is poor, the rains sporadic, the solitary well is 2 kms from the the centre of the village and there is no electricity. They grow some maize here and soya beans in the rainy season; some small, unhealthy clumps of bamboo stretch skywards. Their most lucrative cash crop is a grove of cashew trees - but knowing how much the villagers are paid for each kilo of cashew nuts, I marvel at the price of them in Tesco's. Snotty-nosed, naked children sit comatose with boredom and stare at you for want of anythng better to stare at. Women with water buckets balanced on their heads glower suspiciously at strangers in their midst, as they step unerringly through the dry stones and plastic rubbish on their way to their homes.

There is something quite extraordinary about this Balinese village of Juwuk. I may dare say unique. If you can manage to find your way there at night, braving the evil spirits all around you and the sharp volcanic rock under your feet, and make your way to the Bale Banjar, the community hall, there you will see squatting on the floor and huddled round a Tilley lamp the young men of the village playing cards. "Nothing extraordinary in that." You say. "You've brought us all this way in our imagination to see a group of yobbos playing cards?" But wait! Look again. Look over the shoulders of these velvet-skinned boys. they are playing – wait for it, I need to savour this moment! – they are playing Canasta! Is it possible? Can it be so so far away from the 1950's salons of New York or the students' rooms of Maida Vale but that they should be playing Canasta? But it is so, and the explanation is a trifle mundane.

I cannot call them 'Houseboys'. That term reeks too much of tiffin, bitterly disappointed memsahibs, high collared tunics and exploitation. But Wayan and Suda work for us and live with us in our house in Karangasem. They have been with us a long time and have become an important part of the family which unwittingly, if not unwillingly, I have gathered about me. Wayan and Suda are cousins, as everyone is who comes from Juwuk. (Suda announced the other day that his brother is about to take on a third wife who is the widow of his elder brother. Already the brother of the bridegroom and brother-in-law of the brisk young widow, Suda wants to marry the bride's daughter. So his new sister-in-law will be his mother-in-law and his brother will be his father-in-law. See what I mean about everyone being everyone else's cousin in Juwuk?) And to Juwuk both Wayan and Suda go when they are bidden to attend a ceremony at their temple. At one annual festival called Siwaratri, which according to the Balinese calender is every 210 days (it's 1921 in Bali, by the way - in case you think the whole world has Millenium fever) the men of the village stay up all night to guard the community against evil spirits, in which they all passionately believe. It can be a tedious business keeping the watches of this special night – rather like our All Souls Day – so to while away the uneasy hours Suda and Wayan have passed on to their kinfolk the mysteries of Canasta which I had taught them. High up on the side of this cloud-capped volcano Canasta is now an addictive sport and I have high hopes it might replace cockfighting as the preferred way of loosing your shirt. One interesting aspect of card playing I have observed is this – and I offer it free of charge to any anthropologist frantically searching for a topic to justify his research grant: like the bath water going down the plug-hole, indigenous people south of the equator deal and play their cards anti-clockwise.

After a day of dust and grime in Juwuk, I am desperate to get down to the river below the house. The evening bathe is a balanced ritual between hygienic necessity and social intercourse. Even families with the most splendid bathrooms still walk to the river at twilight, men upstream of the women, to bathe and chat. Who could resist the gossip, or the splashing about, or the washing of one's smalls in the company of others? There is a frisson of sexuality in the air: "Pak Robett! Come and bathe with us!" The women cackle as we pass them. "Saya malu!" I call back laughing (I'm shy!).

The night drops quickly so we bid goodnight to friends and wander back home through the padi terraces by the light of the upturned moon. We pass men with glaring Tilley lamps searching for edible frogs ("Selamat tidur...Selamat tidur...Goodnight"); chameleons scatter from our heavy tread. We disturb a flock of sleeping ducks which by day sift, clean and manure the flooded fields ready for planting. Later, their job of rejuvenating the soil done, they will become Betutu Bebek - smoked duck, a Balinese delicacy. Nothing is wasted in the checks and balances of life on Bali.

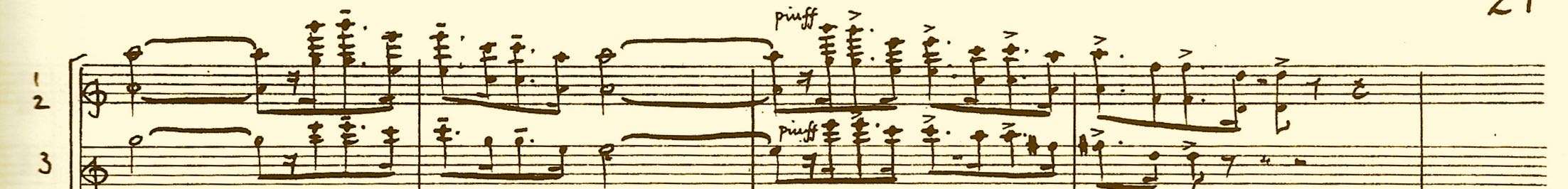

At home our friends Puspa and Ngurah have been waiting patiently on the off-chance we will return. They are silversmiths and have brought gifts of a new design; a treble clef with an amethyst in the curl. "But we cannot accept these!" I protest. "Silakan! Silakan! It is for you Robett and you Ida Bagus. Please take them."

Forgetting me, the three lapse into Balinese. This is not so straightforward as it sounds. Ida Bagus Yudhi is from the Brahmana caste, the priestly caste, the highest caste even above the kings and princes. Puspa is from the Ksatria caste - the rulers and princes. Her husband Ngurah is Wesia, the warriors; whilst 90% of the population are from the lowest caste, Sudra. Each caste has its own distinct language. You think this is complicated enough? There is a fifth language, Kawi, a relative of Sanskrit in which all the dramas and operas are enacted; a sixth - Sanskrit itself - which only the priests know; and yet a seventh: Indonesian - the lingua franca of the 15000 islands that make up this country - in which all Government, television, newspapers and schools operate. Even a simple word like "this" is "ne" in Sudra, in Brahmana it is "niki" and in Indonesian it is "ini". They even count differently in each caste language. Where does that leave me? Nowhere is the short answer - completely at a loss. So in a get-by amalgum of Indonesian and smatterings of English we manage passably.

Wayan always prepares far too much food for our evening meal, so we invite our friends to eat with us. Kare Ayam (curried chicken) tonight with sweet-corn soup and, inevitably, rice. They eat on the floor with the fingers of the right hand deftly rolling balls of rice and morsels together to pop into the mouth. I shovel away more cumbersomely with spoon and fork. I tried their way once at a ceremony. When I got up from my mat, I was mortified to find lumps of roast pork, smoked duck and frostings of rice round me. When there is no table you can't kick it out of sight. We eat in silence, for in Bali it is bad manners to talk during a meal. Garrulous to a fault, I find this impossible and start chattering away. These princes are too polite not to respond but I know I have committed a faux pas.

It is getting late. Time for our guests to return to their family compound. Between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. most Balinese are ranged round sleeping areas in their compounds. Privacy, though often yearned for, is rarely achieved in a village family. We go to bed early too. We leave the verandah to the wheeling bats which pick up the mosquitoes attracted by the lights; we leave the garden to the fireflies – slow-motion tracer bullets weaving through the leaves; we leave the three cats to keep at bay any rats or snakes that may come in from the padi. I set the alarm. It's been a long day and I must work tomorrow. Soothed by elaborate rhythms from the frogs' lullaby in the flooded fields, sleep quickly overtakes us.

We are up at six and the island is already about its business. Wayan prepares breakfast: slices of mango, papaya, pineapple and banana and a squeeze of lime; then toast and marmalade washed down with delicious fresh Kopi Bali - rich and dark coffee grown on the island. On treat days we have Black Rice Pudding: sweet black rice cooked in coconut milk and mashed banana, spiced with fresh ginger and cinnamon.

The working day begins; composing perhaps or e-mails to answer. By 11 a.m. the sun is beating down and sweat makes nonsense of my manuscript. It is too hot to work now. I decide a trip to the swimming-pools at Tirta Gangga is in order. A swim and a gossip with the handful of ex-pats who live in this area sets me up nicely for lunch. Now is the rainy season and clouds begin to billow in the east. After lunch - cucumber soup and tomato salad with my home grown Basil - I and the boys take a siesta. Englishman I may be, but no mad dog. If the mood takes me I tune-in to the scratchy old World Service, wincing each time that oboe doesn't quite make the top note of "Lillibulero." Sandwiched between Radio Australia (fair dinkum but too chatty for me) and Radio Moscow (all Freude durch Arbeiten ) it swells and fades in its own melancholy way.

Before 3 p.m. down comes the rain. This is no misty, grimy drizzle but blocks of water falling out of the sky. Pouring off our thatched roof in torrents, it fills the storm drains in minutes; the roads become streams, the streams become rivers and the rivers become dangerous. The boys and I rush round letting down the rolled bamboo blinds of the open veranda. In high winds these are hopelessly ineffective and water pours in. A vase, top-heavy with one of Suda's creations of hibiscus and frangipani flowers, crashes to the floor. Thunderclaps detonate inside the head. The lights flicker and die; the sub-station has been hit again. Wayan has left the laundry out on the line. Too late to retrieve it now.

Then, as suddenly as it started, the Gods' rage abates. Candles are lit and we sit in the cool, sweet air as dusk envelopes us. After rains like this the sunset is unbelievably beautiful, so we decide to climb the top of the ridge behind the house to witness it fall behind Gunung Agung, the great volcano. A huge red disc appears under gigantic anvils of cloud and framed by palm fronds and the growing rice. Our faces glow golden. Nothing in the world can rival this moment. At this latitude the sun sinks fast and we are palpably aware of the earth's rotation. Only a few minutes of wonder and it is gone.

Good-bye sun, Selamat Jalan. It is 11 in the morning in Europe. Will they see you there? Will my friends in America wake-up to you later? Soon you will be round again, coming over the hill behind the house. We shall greet you again from our terrace. But now it's time for a few rounds of Canasta.